PLATES.*

|

Facing |

| View of the Harbour and Town of Valparaiso. |

Frontispiece |

| U.S. Frigate Potomac. Passing Mount Vernon. |

11 |

| View of Rio Janiero. |

35 |

| Cape Town and Table Mountain. |

73 |

| Action of Qualla Battoo, as Seen from the Potomac at Anchor in the Offing: J. Downes Esq. Commander Feb. 5, 1832. |

121 |

| View of Canton. |

337 |

| The Usual Walking Costume of Lima. |

439 |

| View of Lima, from Mr. Christoval – Overlooking the Port and Harbour of Callao. |

443 |

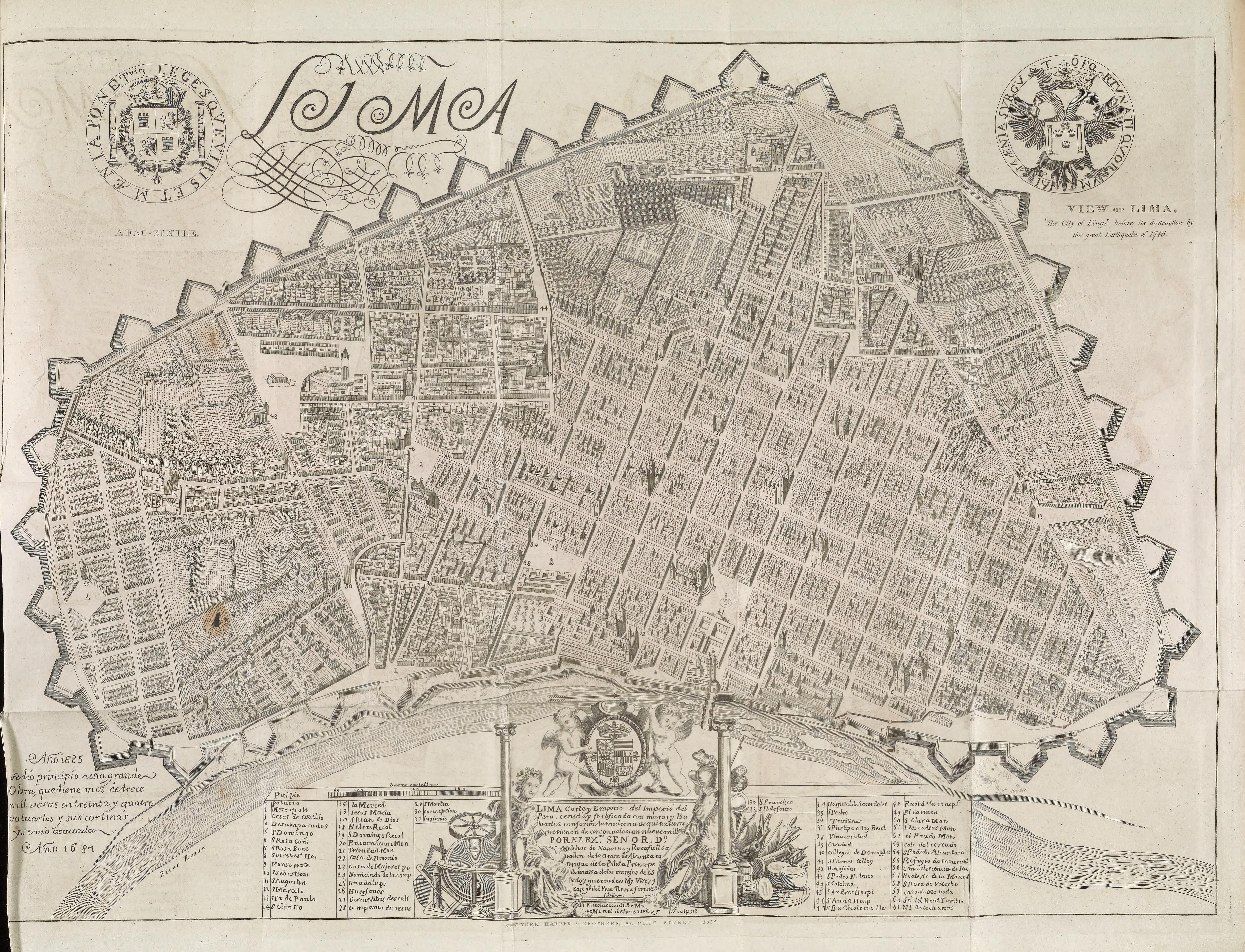

| View of Lima. 'The City of Kings' before its destruction by the great Earthquake of 1746. |

457 |

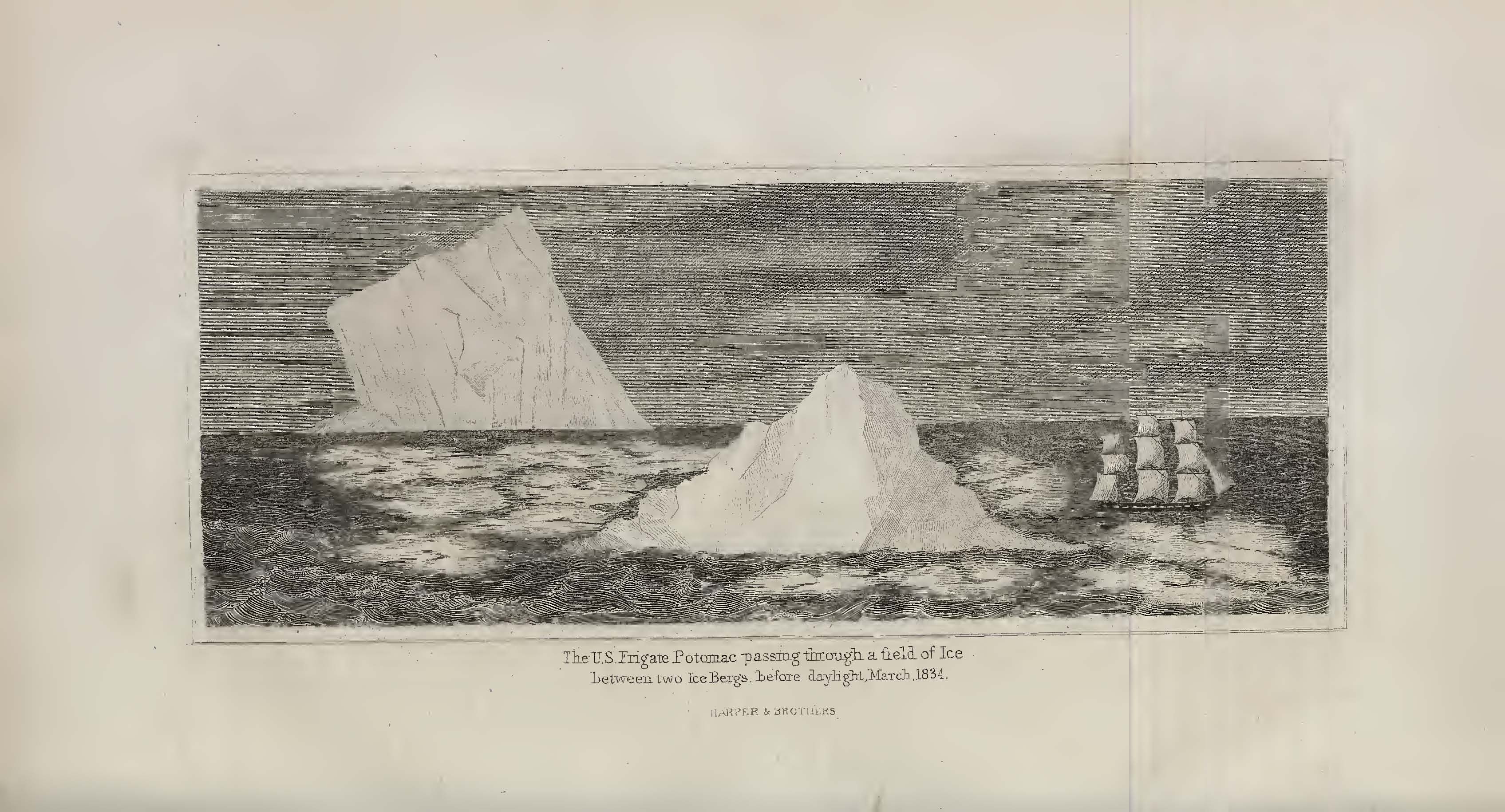

| The U.S. Frigate Potomac passing through a field of Ice between two ice Bergs before daylight, March 1834. |

517 |

INTRODUCTION.

In the month of October, 1829, I sailed from the city of New-York in the brig Annawan, N. B. Palmer captain, to the South Seas and Pacific Ocean. The particulars of this voyage, and the circumstances which led to it, as well as those of my subsequent travels by land through the Republic of Chili, and the Araucanian and Indian Territories to the south, will be given to the public in another volume. Suffice it here, that I was at Valparaiso in October, 1832, just three years from the commencement of my voyage, when Commodore Downes arrived at that place, from the coast of Sumatra and some of the principal ports in the East Indies.

He had been for some time expected on that station; and early in the afternoon on the day of his arrival, it had been announced by telegraph, from the high hill which overlooks the town, that a large ship was in the offing. An hour passed away, and the signal announced a man-of-war, southwest from Playa Ancha, with all sail set, standing directly for the port. The wind was fresh, and she approached rapidly. The stripes and stars were seen waving from the mizzen peak of a stately frigate, which was now pronounced by all to be the Potomac. She entered the harbour late in the afternoon, making several seamanlike tacks against a strong southerly breeze. Crowds gathered upon the beach, and the Americans in port evinced emotions of pleasure, as each one felt that the strong and protecting arm of his government was near him.

On the following day I went on board, with the view of visiting several of the officers with whom I had been previously acquainted. Here I received an invitation from the commodore to join the Potomac as his private secretary, the

|

|

gentleman who had previously filled that station having died at sea. This is a pleasant birth on board a flag-ship, and I accepted it, as the stay of the commodore on the station promised me a fine opportunity to improve my knowledge of the institutions, natural capacities, commercial resources, and political condition and prospects of so large a portion of South America, which hitherto I had not been able to visit.

The cruise of the Potomac, thus far, had been one of great interest, and the services performed by her of high importance to our commercial interests in the east. News of her arrival at the Island of Sumatra, and her action with the Malays, reached the United States in the early part of July, 1832, at which time Congress was still in session.

Partial statements relative to the occurrences at Quallah-Battoo had been published in the journals of the day; and those papers had now reached the Pacific. The attention of Congress had been called to the subject. Mr. Dearborn, of the House of Representatives, on the 12th day of July, submitted a resolution calling on the President for the instructions under which Commodore Downes acted, in his attack on the Malays of the Island of Sumatra. The resolution was adopted without objections from any quarter; and before the adjournment of the House on the next day, a communication covering the instructions was received from the President, recommending that these papers should not be made public until a full report of the proceedings at Quallah-Battoo should be received from Commodore Downes; intimating, that the vague rumours and partial statements before the public relative to the transactions at that place, when compared with the instructions under which that officer acted, might create an unfavourable prejudice against him in the public mind, which ought to be guarded against during his absence from the country, and until all the circumstances which influenced his mind should be authentically known.

On the reception of these papers, the House of Representatives referred them to the Committee on Foreign Affairs; and after being examined by that committee, the latter unanimously concurred with the President, that the instructions ought not to be published until official, full, and accurate information was received, as to the manner in which the instructions had been executed.

|

|

Without taking any further measures on the subject, Congress adjourned on the 16th of July.

It seemed evident that the public mind, though always just when correctly informed, had, in this instance, been misled by partial statements and publications of irresponsible persons, who attempted to pronounce upon the merits of the proceedings at Quallah-Battoo without knowing, or having it in their power to know, a single motive which had influenced the mind of the commodore during his stay on the Malay coast.

These circumstances, together with the extent and nature of the Potomac's voyage, — the direct manner in which the attention of Congress and the country at large had been thus early called to it — seemed to require that an authentic record should be prepared; in which not only the incidents of the voyage, but the public considerations which led to it, — and the motives which, at different periods of the cruise, had operated on the mind of its commander, in carrying into execution the views and instructions of the government, should be faithfully preserved.

It was at this time, and under these circumstances, and with the express sanction of the commodore himself, that I undertook the task of preparing this record — in the execution of which every facility was offered me. Though more or less indebted to most of the officers of the higher grades for some incidents of the voyage, noted down by them on going below from their watches on deck, yet I feel it my duty especially to acknowledge my obligations to Lieutenant R. Pinkham and Acting-lieutenant S. Godon. The former, an intelligent officer, had kept a copious record, day by day, as the incidents of the voyage passed before him, which notes were placed in my hands. The latter, a young officer of high promise, had been an attentive observer, and recorded what he saw. For days, and weeks, and even months, he was ever ready to pore over the charts with me; and, by a vivid recollection, to recall the rich tints of a tropical sky, the phosphorated gleamings of the ocean, or the mellow hues of the landscape among the "summer isles." , The commodore's private journal was also in my hands; while the daily communication and unrestrained intercourse which existed between us, enabled me to speak with knowledge of all the public considerations which guided the movements of the frigate under his command.

|

|

In comparing what I had written from these authentic sources with the journal kept by N. K. G. Oliver, Esq., the commodore's private secretary during the early part of the voyage, I found not a line to erase, and scarcely a word to add. In addition to all these advantages combined, the length of residence on board of the Potomac, in the midst of those who had been eye-witnesses and actors, by whom the incidents of the past were so often brought in review before us, I found no difficulty in filling up even the lights and shades of the whole picture, up to the period at which I joined the frigate — some twenty months previous to her return to the United States. Being thus familiar with the whole subject, I have found it most convenient to adopt the first person and present tense in the narrative, from the beginning to the end of the cruise.

Where I have travelled beyond the record of the voyage, and say something on our commercial interests in the east, of its history, present condition, and means of its further extension; of sailing directions and the monsoons; of the Chinese, their peculiarities and pagodas; of the Sandwich and Society Islands, their population, missionaries, and foreign residents and traders; of the great Pacific whale fleet, the present derangement of this important branch of commerce, and the necessity of some action on the part of the United States government for the preservation of this interest; of the people of South America, their political and social institutions; of the controversy with the Argentine Republic in relation to the Falkland Islands; or of Rio and the empire of Brazil — I repeat, that what I say on any of these subjects, or others of a like nature, will be at all times on my own responsibility.

A short time after the return of the Potomac, I addressed a line to the Honourable Levi Woodbury, at that time Secretary of the Navy, requesting permission to examine certain public documents on file in the department, from our commercial agents in different parts of the world where the Potomac had touched, and which might contain matter useful in rendering more perfect the details of my work. To this request I received the following reply: —

|

|

"Navy Department, 9th June, 1834.

"Sir,

"Your letter of the 5th inst. has been read; I shall be happy to oblige you with the inspection of any papers in this department which are not confidential, and may be useful to you in your contemplated publication.

"I am, very respectfully, yours, &c.

(Signed) "Levi Woodbury.

"To J. N. Reynolds, Esq."

The same facilities, in answer to a similar request, were politely proffered me by the Honourable John Forsyth, Secretary of State.

One important object still remained to be accomplished, and without which the work would be very defective; and this was to obtain a copy of the official and public documents connected with the cruise. As there had been special, as well as general instructions from the department to Commodore Downes, I deemed it my duty to inform the latter of my application to the department for copies of these papers, and received from him the following reply; a copy of which I enclosed to the Secretary of the Navy: —

"Charlestown, 26th August, 1834.

"Dear Sir,

"In answer to your note of the 19th inst., I have to state, that your having undertaken to prepare a Journal of the Potomac's Cruise while on the Pacific station, with my knowledge and approbation, and so often having held free communication with me on the subject; and knowing, as you do, my wish, that whatever is published should be authentic, I can of course have no objection that my instructions from the Navy Department, under which I acted while on the coast of Sumatra, with all official papers and reports made or received during the cruise, should be placed in your hands, with the sanction of the department, for the illustration of your book.

"Yours, very sincerely,

(Signed) "John Downes.

"J. N. Reynolds, Esq., New-York."

|

|

"Navy Department, September 1st, 1834.

"Sir,

"Your letter of the 27th ultimo has been received, enclosing a copy of Commodore Downes' letter to yourself, consenting to your application for a copy of his instructions.

"The Secretary of the Navy will be here in a few days, when your request shall be submitted to him.

"I am, respectfully, yours,

(Signed) "John Boyle,

"Acting Secretary of the Navy.

"J N. Reynolds, Esq., New-York."

"Navy Department, 27th September, 1834.

"Sir,

"Your letter of the 20th inst. has been received; Commodore Downes has the permission of the department to furnish you with copies or extracts, as may be most desirable to you, of his instructions and reports in relation to his operations at Quallah-Battoo.

"I am, very respectfully, yours,

"Mahlon Dickerson. "P. S. Commodore Downes has this day been authorized to furnish the above papers.

"J. N. Reynolds, Esq., New-York."

With such credentials in my hands, and the consciousness of a well intended effort in my heart, I would respectfully make my debut before the American public — uninfluenced by vain ambition, unembarrassed by ill-timed diffidence. If my plain narrative of maritime incidents, perils, and achievements —

|

"All that occurred, part of which

I was * * * * * * * * * *"

|

has no pretension to the charms of fine writing, it has at least the honest merit of truth and fidelity in the delineation of such facts as it purports to record.

|

U.S. Frigate Potomac. Passing Mount Vernon.

[Click to enlarge image]

|

V0YAGE

OF THE

UNITED STATES FRIGATE POTOMAC.

CHAPTER I.

| Object of the Cruise — Selection of the Frigate — Her departure from Washington — Reflections on passing Mount Vernon — Descending the River — Hampton-Roads — New-York — Additional Orders — Final Departure — Sandy Hook — Dismissing the Pilot — Tributes of Affection.

|

The United States frigate Guerriere, under the command of Commodore Thompson, having nearly fulfilled her term of service on the west coast of South America, in the Pacific, it became necessary to despatch another ship-of-war to relieve her on that important station. For this purpose, early in the year 1831, the Navy Department selected and for the first time put in commission the frigate Potomac, then lying at the navy yard in Washington city. She had been built at the same place ten years previously, and is of the first class of frigates, a fine model, and commanding, warlike appearance.

The officers intended for the cruise had received their orders in the early part of the year; and in the month of March a number of them had repaired on board, and reported themselves to the first lieutenant as ready for duty. On the 10th of May Commodore Downes was notified of his appointment to the command of the Potomac, then fitting for sea at the navy yard at Washington, for the purpose of joining the squadron in the Pacific. Being at that period employed on other public duties, he was only able to visit the frigate once previous to her removal from the seat of government. He then left her in the

|

|

12 |

VOYAGE OF THE POTOMAC.

|

[June, |

charge of the executive officer until she should, arrive in the port of New-York.

During the whole month of May the most active preparations were going on aboard, so that by the 31st she was hauled out from the navy yard wharf, and by the aid of two steam-boats was towed over the bar, and moored head and stern off the mouth of the eastern branch of the Potomac. Previous to her removal from the navy yard, she had been visited by the President and Honourable Secretary of the Navy.

The period from the 1st to the 14th of June was exclusively occupied in the outfits of the ship, and in getting off stores and various other articles; though all the sea-stores could not be taken in at this place, owing to the want of a sufficient depth of water in many parts of the Potomac river. In the mean time the ship had undergone a material change in her appearance and internal arrangements, and not only began to assume more of the regularity of a man-of-war among her inmates, but in every other respect bespoke preparation for a distant voyage. She was at this time, 15th, again visited and inspected by the Honourable Secretary of the Navy and Navy Commissioners.

On the following morning, the 16th, orders were issued to the commanding officer to proceed with the Potomac down the river to Norfolk. The anchor was immediately weighed, and the frigate put in motion by the aid of a fine steam-boat selected for towing her down the river to Hampton-Roads,

The movements of a vessel of such dimensions down the intricate channel of a river which rises so many leagues from the ocean, was not only calculated to produce a painful anxiety, but was, in fact, a matter of no small responsibility. The city of Washington, it is well known, is that point in the United States to which the largest vessels can be navigated the farthest into the interior of the continent. This single fact evinces the wisdom and foresight of him whose advice thus located the capital of the empire which he founded.

Neither sectional partiality nor prejudice, it appears, had the least influence in determining this important matter; for the father of his country did not recommend the spot where the city of Washington now stands, until he had bestowed great and unwearied pains, and made laborious and interesting reconnoissance

|

|

1831.] |

LOCATION OF THE CAPITAL.

|

13 |

of the country adjacent; and though the conflicting claims of other states, particularly those of Pennsylvania, were strongly urged against the measure, yet, fortunately for the nation, the popularity and influence of Washington surmounted every obstacle, and permanently fixed the seat of the general government in, perhaps, the best possible position that could be selected in any part of the United States.

It may be mentioned as a curious coincidence, and a fact not generally known, that the present permanent seat of our national legislature is contiguous to the very spot where formerly were lighted the council-fires of the Powhattans, the most prominent, numerous, and powerful nation of red men in Virginia; and on the banks of the Potomac, extending from the shores of Chesapeake to the Patuxent. These people lived under a royal government, their despotic monarch being the father of the celebrated Pocahontas. The valley at the foot of Capitol-Hill, washed by the Tiber Creek, the Potomac, and the Eastern Branch, was, as we are informed by tradition, periodically visited by the Indians, who named it their fishing-ground, in contradistinction to their hunting-ground. Here, the tradition adds, the aborigines assembled in great numbers, in the vernal season, for the double purpose of preserving fish and consulting on the affairs of the nation. Greenleafe's Point was their principal camp, and the residence of the chiefs, where councils were held among the various tribes thus gathered together. This tradition was doubtless familiar to Washington.

It has been said above that a more eligible site for the seat of our national government could not have been selected. It is true that a hostile fleet has once violated the purity of these waters, conveying a sufficient military force to invest the capital of the nation, from which most of its physical strength had been drawn to defend points which seemed more exposed to immediate attack. But we were then a young, weak, and divided people, contending with a gigantic power. Things have changed since that period; and the waters which have borne the warlike Potomac with her frowning batteries so many leagues from the interior to her destined element, can scarcely again, in the course of human events, be agitated by a hostile keel.

Under the old confederation, by which the states were nomi-

|

|

14 |

VOYAGE OF THE POTOMAC.

|

[June, |

nally bound together, Congress was dependant upon the several sovereignties for "a local habitation," and might have been virtually dissolved by the mere refusal to permit the occupation of public buildings. This inconvenience was provided for, probably at the suggestion of Washington himself, in the eighth section of the first article of the Constitution, which gave express power to Congress "to exercise exclusive legislation in all cases whatsoever, over such district (not exceeding ten miles square) as might by session of particular states and the acceptance of Congress become the seat of the government of the United States."

In accordance with this provision, the states of Virginia and Maryland ceded to the United States their jurisdiction over a district of ten miles square, situated on both sides of the Potomac, nearly two hundred miles from its mouth. This cession was formally accepted by the United States government, in an act of Congress passed on the 16th of July, 1790; and ten years afterward, during the presidency of John Adams, the government was removed thither, and permanently established in the infant city called after the deathless name of its patriotic founder. On the 3d of May, 1802, Congress passed an act by which the city of Washington became incorporated; the appointment of mayor being vested in the president annually, and the two branches of the council elected by the people in a general ticket. By a new charter granted by Congress in 1820, the mayor is now elected by the people for a term of two years. The city is rapidly increasing in wealth and population.

Our gallant, though as yet untried frigate, moved gracefully and majestically upon the waters of the river whose name she bears; and passing Mount Vernon with flag half-mast in token of respect for the sacred relics which were there deposited, she again came to anchor without accident at India Head.

The reader is doubtless aware that the consecrated spot alluded to is situated on the Virginia side of the Potomac river, the course of which at this place is nearly southwest, though its general course is to the southeast. Mount Vernon, therefore, is on the western bank of the river, and rises at least two hundred feet above its surface. It is about fifteen miles below the city of Washington, and eight miles from Alexandria. It was so named in honour of Admiral Vernon, in whose celebrated expedition

|

|

against the Spaniards Washington's brother Lawrence served; and he was the original proprietor of this delightful sylvan retreat. It afterward passed into the general's hands, and it was here that he resided when retired from the cares and labours of public employment; and it is here that his ashes now repose, together with those of his connubial partner, and several relatives of the family. To visit this place is deemed a sort of pious or rather patriotic pilgrimage, which few would willingly neglect to make at least once in the course of their lives, should circumstances call them to the seat of government.

The mansion in which Washington resided till his death is a plain edifice of wood, cut in imitation of freestone, two stories high, surmounted by a cupola, and ninety-six feet in length, with a portico in the rear, overlooking the river, extending the whole length of the building. The central part of this edifice was erected by Lawrence Washington, who named it as before mentioned; the two wings were afterward added by the general, who caused the ground to be planted and beautified in the most tasteful manner.

The house fronts northwest, looking on a beautiful lawn of five or six acres, with a serpentine walk around it, fringed with shrubbery and planted with poplars. The tomb, or family vault, in which rest the hero's remains, is about two hundred yards southwest from the house, and about one hundred and fifty from the river bank: "A more romantic and picturesque site for a tomb," says a late writer, "can scarcely be imagined. Between it and the river Potomac is a curtain of forest-trees, covering the steep declivity to the water's edge, breaking the glare of the prospect, and yet affording glimpses of the river even when the foliage is thickest. The tomb is surrounded by several large native oaks, which are venerable by their years, and which annually strew the sepulchre with autumnal leaves, furnishing the most appropriate drapery for such a place, and giving a still deeper impression to the memento mori. Interspersed among the rocks, and overhanging the tomb, is a copse of red cedar; but whether native or transplanted is not stated. Its evergreen boughs present a fine contrast to the hoary and leafless branches of the oak; and while the deciduous foliage of the latter indicates the decay of the

|

|

16 |

VOYAGE OF THE POTOMAC.

|

[June, |

body, the eternal verdure of the former furnishes a beautiful emblem of the immortal spirit."

La Fayette's visit to the tomb of Washington, as described by M. Levasseur, is interesting and touching. "As we approached," says he, "the door of the tomb was opened. La Fayette descended alone into the vault, and a few minutes after he reappeared with his eyes overflowing with tears. He took his son and myself by the hand, and led us into the tomb, where by a sign he indicated the coffin of his paternal friend, alongside of which was that of his companion in life, united for ever to him in the grave. We knelt reverently near his coffin, which we respectfully saluted with our lips; rising, we threw ourselves into the arms of La Fayette, and mingled our tears with his."

|

"Flow gently, Potomac! thou washest away

The sands where he trod, and the turf where he lay,

When youth brush'd his cheek with her wing;

Breathe softly, ye wild winds, that circle around,

That dearest, and purest, and holiest ground,

Ever pressed by the footprints of spring.

Each breeze be a sigh, and each dewdrop a tear.

Each wave be a whispering monitor near.

To remind the sad shore of his story;

And darker, and softer, and sadder the gloom

Of that evergreen mourner that bends o'er the tomb,

Where Washington sleeps in his glory."

Brainard.

|

The subject of this digression will naturally plead its excuse. While lying in sight of Mount Vernon in a ship-of-war, comprising within her oaken walls more effective force than the whole American navy could display at the time this beautiful spot first received the name it bears, such reminiscences occurred too forcibly to the mind to be passed unnoticed. But the anchor was again weighed, and our new ship-of-war soon left Mount Vernon far in the distance.

After a passage of several days, requiring great vigilance, and without encountering any serious accident, the Potomac came to anchor on the afternoon of the 23d June in Hampton-Roads, about eight miles below Norfolk, which is the most commercial town of Virginia, and is defended by several forts, the most im-

|

|

1831.] |

DEATH OF EX-PRESIDENT MONROE.

|

17 |

portant of which is on Craney Island, near the mouth of the Elizabeth river, about five miles below the town. The United States commissioners who were appointed in 1818 to survey the lower part of Chesapeake Bay, reported that Hampton-Roads, though extensive, were capable of adequate defence, so as to prevent the entrance of an enemy's fleet. We therefore trust that our national metropolis will henceforth be secure from invasions.

The general instructions of the secretary of the navy to Commodore Downes, as commander of the Potomac and of the Pacific squadron, are dated on the 27th of June, 1831. He was ordered to proceed to New-York by the 1st of August, if possible; and there receive on board the Honourable Martin Van Buren and suite, the recently-appointed minister to the court of St. James, who was to be landed at Portsmouth, or some other convenient port in the British channel. The commodore was then directed to make the best of his way to the Pacific Ocean by a passage round Cape Horn, first touching at Brazil. These instructions contain full and official directions as to the steps to be taken for the protection of American commerce and sustaining the honour of the American flag, as well as for increasing the domestic resources of our own country, by obtaining and preserving such foreign staple productions as might be naturalized in our own soil. These instructions, so creditable to the department and to the character of our country, are given at length in the Appendix.

Our frigate lay in Hampton-Roads until the 15th of July, during which period all hands were busily employed in taking on board such necessary stores as could be procured at this place. Here her officers first received the intelligence of a third point to a coincidence of a very remarkable character. On the 4th of July, the anniversary of our national independence, James Monroe, the fifth president of the United States, breathed his last, in the city of New-York, at the residence of his son-in-law, Samuel Governeur, Esq. This event had been for some time expected, and was several days previous to his death momentarily looked for. His spirit, however, was permitted to linger in the body until his country's birthday came round; and he departed while a grateful nation, for whose independence he had fought and bled — a nation which venerated him while living, and which

|

|

18 |

VOYAGE OF THE POTOMAC.

|

[July, |

hallows his memory now as in the foremost rank of its benefactors — was holding its jubilee! Thus, by a coincidence for which it would be difficult to find a parallel in history, three patriots of the revolution, who had successively graced the presidential chair, were called away to a more permanent state of existence on the glorious anniversary of the independence which they had so zealously laboured to achieve. The death of James Monroe on the 4th of July, 1831, completed the threefold miracle that was doubtless intended to convince the most skeptical of the divine superintendence of that providence which raised up these three statesmen and patriots for the purpose of achieving the work of independence. "Did this event stand single in our annals," says an orator of much deserved celebrity, "were it unconnected in our memories with the deaths, on a former anniversary of the same glorious day, of two of his illustrious predecessors, — even then a similar removal of the deceased would have been deemed admonitory, and would have commanded a solemn and appropriate notice. But following, as it does, that signal union in their flight from this world of the immortal spirits of Adams and Jefferson, the departure of Monroe must impress us with an awful sense of a divine interposition, and awaken a lively gratitude for the favour and protection of an overruling providence."

On the 15th of July the Potomac, in conformity to orders, sailed from Hampton-Roads for the port of New-York, for the purpose of completing her outfits of all kinds, and also to receive her commander on board; who, having received his orders from the department, was nearly ready to take the immediate command. Nothing material occurred during the passage of the frigate to New-York. On Wednesday, the 20th of July, she was announced by telegraph as being anchored outside the bar, waiting for a fair wind to enter the harbour. On the following day she proceeded up the bay in gallant style, and came to anchor off the Battery, in the Hudson river.

Although it was for some time intended that the Potomac should proceed from New-York to England, in order to convey our newly-appointed minister, the Honourable Martin Van Buren, to the court of St. James as before stated, this arrangement, it will be seen, was ultimately abandoned, and Mr. Van Buren proceeded to England in the regular packet-ship President, which

|

|

1831.] |

ADDITIONAL INSTRUCTIONS.

|

19 |

sailed on the 9th of August; while new and additional orders were issued from the navy department, which totally changed the intended course of the Potomac, and sent her round the southern cape of the opposite continent.

On the 4th of August the United States frigate Hudson, Captain Cassin, arrived in New-York from Rio Janeiro, via Bahia, having left the latter place on the 2d of July. There were now three commanders' pennants floating over the waters of this port; viz. the blue of Commodore Chauncey, who commanded the station; the red of Commodore Downes, who commanded the Potomac; and the white of Commodore Cassin, who commanded the Hudson; — blue, red, and white being the order of the navy.

About the middle of July information was received in the United States of the piratical attack which had been made upon the ship Friendship, of Salem, on the coast of Sumatra, in the month of February preceding; the Malays having treacherously seized that vessel, and massacred part of her crew, who were receiving on board a cargo of pepper. The particulars of this unparalleled outrage on the United States flag and the lives and property of her citizens, will be given in detail in its proper place, where a chapter shall be devoted exclusively to the subject. The public were unanimous in calling for a redress of such an atrocious grievance, and the Potomac was now designated by government to perform that service instead of proceeding directly to her original destination. The route of the frigate to her station in the Pacific, as contemplated in the previous instructions, was therefore immediately changed, that measures might be promptly and effectually taken to punish so outrageous an act of piracy; Mr. Van Buren having, for this purpose, magnanimously relinquished his purpose of taking passage in the frigate, as the landing him in England would delay her arrival at the scene of this perfidious attack.

Messrs. Silsbee, Pickman, and Stone, of Salem, addressed a letter to Washington, dated on the 20th July, 1831, requesting that measures might be adopted by government for the punishment of the offenders in the case of the Friendship; but before this letter had reached Washington, arrangements for that purpose had been put in progress by the secretary of the navy on the 19th of that month, and a letter written to Salem on the subject on

|

|

20 |

VOYAGE OF THE POTOMAC.

|

[August, |

the 22d, of which they were apprized by another letter dated the 25th of July, in reply to that of the 20th before referred to; in which they were requested to furnish the department with such local information relative to the region where the outrage was committed, as might become essential in seeking indemnity or inflicting punishment on the perpetrators. A copy of this letter will also be found in the Appendix. Through the medium of this correspondence the government obtained the services of a gentleman of Salem, who had been personally concerned in the pepper-trade on the coast — was on board the Friendship when attacked, and was well acquainted with that part of Sumatra.

The preparations being completed, additional instructions on this branch of the cruise were given to the commander, as before mentioned, by the secretary of the navy, on the 9th of August. In order to appreciate the judgment and caution with which these instructions on so delicate and important a subject were drawn up, as well as to enable the reader, in the sequel, to judge of the faithful and officer-like manner in which they were carried into execution, it will be necessary for him to recur to the copy which we have been permitted to insert at length in the Appendix. By these instructions it will be seen he was directed to proceed from Rio Janeiro to the east by the Cape of Good Hope, to call the treacherous Malays to an account, and redress our grievances in that quarter; and from thence, after visiting certain ports in the Chinese Seas, to cross the vast Pacific, and take command of the squadron on the west coast of South America.

With reference to the outrage in question, the public press evinced a sensitiveness which did honour to the editorial corps. Only a few days previous to the sailing of the Potomac, many articles on the subject appeared in the daily papers, from one of which the following extracts are copied: — "As far as public sentiment can be collected from the newspapers and from general conversation, it appears to be the unanimous wish of the nation that one or more of our ships-of-war should be despatched to the western coast of Sumatra, to look after our commercial interests in that remote sea, and punish the natives for the outrage recently committed upon the ship Friendship, of Salem." In the same article it is added, "A high-handed outrage has been committed, and if it be suffered to pass by unavenged, we know not how

|

|

1831.] |

TRIBUTES OF AFFECTION.

|

21 |

many others may occur. The approaching departure of the Potomac will afford the government an opportunity of intrusting the expedition to an intelligent, active, and gallant officer, who, we apprehend, would teach these piratical vagabonds such a lesson respecting American manners and customs as would hereafter induce them to mend their own."

Although Commodore Downes had hoisted his broad pennant on board of the Potomac on the 24th of July, he was still absent on business until the 23d of August. During this period the Potomac lay at anchor off Castle Garden, in the North river, and every arrangement deemed necessary for a long and distant voyage was completed.

The wind, which for several days had blown from an unfavourable quarter, chopped round on the morning of the 24th of August,* and gave us a fine light breeze from the northwest. "All hands up anchor, ahoy!" was the cheerful cry which passed through the ship before five o'clock, ere the rising sun had gilded the tallest spires of the city. This summons was succeeded by a scene of bustle and excitement which can only be realized by one who has witnessed its effects on the officers and crew of a man-of-war bound on a distant cruise. The Potomac's canvass wings were suddenly expanded, as if by magic, and the gallant vessel moved slowly but gracefully from her anchorage down the bay, until Sandy Hook lighthouse bore east by south half-south, when she' was again brought to anchor. . â–

The wind and tide both favoured the departure of the Potomac on the morning of the 26th, and by eight o'clock she had passed the bar with a fine leading breeze. The maintopsail was now laid to the mast, while the pilot made his hasty preparations to depart. At such a moment most vessels, but, perhaps, especially a man-of-war, present a busy and interesting scene. There had been ample leisure for writing during the days of detention by contrary winds; but the last moment on such occasions must always be embraced; and the state-rooms of the officers, the ward-room, steerage, and cockpit, are occupied by writers penning hasty adieus, despatching the last little earnest of continued affection. If this be a mere matter of feeling, be it so; there is something sacred in it which the warm heart can always appreciate — for a line written at the moment the noble vessel lies

|

|

22 |

VOYAGE OF THE POTOMAC.

|

[August, |

shaking in the wind, and about to bound fearlessly on her destined track, must always possess a value that under no other circumstances can be imparted to it.

The pilot, having taken charge of these sacred scraps, hastened to his little boat, which had been dancing on the undulating billows near the Potomac like another nautilus during the whole / of the morning. The ship was now filled away, and every drawing sail set, bearing to the south and east.

There have so often pretty things been said, and so many fine.changes rung on language in describing the feelings of the heart on bidding to our "native land good night," that we shall attempt nothing of the kind here. We are well aware, however, that thousands are daily taking their departure without evincing any unusual emotions about it; and yet we do really believe no one can thus depart without experiencing emotions which do credit to the human heart.

In four hours, and they were short ones, the last faint lines of the highlands had vanished, and the active duties to which many were called seemed to relieve them from the recollections of home. But it is the youth, the young ' "reefers," who have for the first time left the parental fireside, who are likely to feel much in moments like these. Though previous to their embarcation they think they have a tolerably correct idea of the privations and toils of the mariner's life, and feel their minds well fortified to combat the most untoward events; yet, when in the space of a few hours they find themselves tossing upon the mighty deep, and that deep begirt only by the open horizon, the ship dashing with each freshening breeze, with accumulated velocity, from all their young affections hold dear; 'tis then that the heart, desponding, shorn of every pride, feels its frailty, and owns how strong is that cord which binds to country and home.

They now remember with the liveliest feelings and emotions of filial affection, that the kind admonitions of a father were really and in truth kind. Bygone hours and days, spent from home with convivial friends, or in search of some momentary pleasure, now present themselves to their lively imaginations, shaking their "gory locks," upbraiding them with their time mispent — or, if not entirely mispent, they feel they might have been much better employed in the society of a fond mother or sister — of those

|

|

1831.] |

FINAL DEPARTURE.

|

23 |

whom they now sensibly feel are and ever must be the truest objects of their affections and obedience.

Having gained a sufficient offing, the anchors were, as is usual, securely stowed, cables unbent and coiled in, their respective tiers, and, in the language of a thrifty housewife, as well as of the sailor, every thing "made snug"

|

|

24 |

VOYAGE OF THE POTOMAC.

|

[August, |

CHAPTER II.

| Sea-sickness — The Gulf-stream — A Storm at Sea — Cape de Verds — St. Antonio — A Whale-ship — Trial of Speed — Crossing the Equator — Rio Janeiro — Courteous Reception of the Frigate.

|

On the second day following her departure from Sandy Hook, a tumbling sea caused an irregular pitching and rolling motion of the vessel, peculiarly unpleasant to those who were unaccustomed to the turbulent domains of Neptune. The certainty, however, that sea-sickness is not fatal in its effects, and that, sooner or later, a restoration to health will ensue, has sometimes encouraged others, whose stomachs are proof against this scourge of the "fresh man of the sea," to sport in wanton mood with the dejected feelings of the sufferer. Yes, we repeat, sufferer, for woful experience has taught, that, of all the "evils which flesh is heir to," none is so unpleasant, for the time being, as sea-sickness. The spirits droop, the heart sickens — a total indifference to life, death, friends, home, country, succeeds — until every thing seems swallowed up in that nauseating stupor which preys upon the very spirit itself! '

The autumnal equinox was now fast approaching, a season of the year which frequently introduces itself into the North Atlantic with storms and tempests, and even violent and destructive hurricanes.

As the Potomac approached the gulf-stream, she underwent the usual preparation for storms and squalls, so generally met with in this portion of the Atlantic; so usual, indeed, that it has become proverbial —

|

"That in the stream

The lightnings gleam,

And Boreas blows his blast."

|

The commodore had hoped to escape every thing like a gale, quite content to try the qualities of his ship for sailing with fine

|

|

1831.] |

STORM WITH VIVID LIGHTNING.

|

25 |

breezes and clear weather. In this, he was disappointed; as, on the twenty-eighth, the wind, which had for some hours prevailed from the eastward, with rain, partially died away, the sky became overcast with threatening appearances, which the wary and experienced seamen very soon recognised as the prelude to the approaching gale. No light sails were spread to woo the fickle breeze, but topgallant and royal yards were sent upon deck, and the flying jib-boom housed. As the night set in, the wind increased.

|

"Now, while on high the freshening gale she feels,

The ship beneath her lofty pressure reels.

Th' auxiliar sails, that court a gentle breeze,

From their high stations sink by slow degrees."

|

The courses were hauled up, jib stowed, mizzen-topsail furled, spanker lowered, and the fore and main-topsails double reefed. It is at such times, and on such service as this, that the brave daring, the recklessness of danger, the ambition to be foremost when duty calls, no matter where, shine most conspicuous in the character of the thorough-bred and true sailor.

|

"'Tis his the harder toil to share,

To reef, to furl the sail;

To face the, lightning's lurid glare,

And brave the sweeping gale."

|

Indeed, the true sailor takes pleasure in doing his duty amid real dangers, when he feels that the "superior officer set over him" is competent to judge whether or not that duty is performed in a seaman-like manner. .

The gale, for by eight, P. M., it had the strength of one, increased every moment till ten, when the ship was brought to, head to the southward and westward, under close-reefed fore and main-topsails, and courses furled; when, at the same time, the foretopmast-staysail was hauled down, and the fore-storm staysail set.

Soon after midnight the gale had increased to almost a perfect hurricane, and the ship was pressed down by the irresistible blast, until relieved by furling the close-reefed fore-topsail, and setting the main and mizzen-storm staysails. From twelve to

|

|

26 |

VOYAGE OF THE POTOMAC.

|

[September, |

four, A. M., it blew with a violence seldom witnessed, even in this region of tempests. The sea, which the evening before had been comparatively smooth, now rolled in mountains before the storm. Seldom had the electric fluid assumed such a variety of colours in so short a period of time. Though the flashing was incessant, yet in the space of a few seconds were exhibited, in the coruscations of the subtile fluid, all the varying colours of the rainbow; twice did it pass down the fore-conductor, assuming on the second descent a most singular appearance. As the fluid followed the conductor, at each link of the chain, an electric spark was thrown off of the deepest red, while the livid line of light simultaneously marking the direction of the conductor, rendered it a singular phenomenon.

The rain, at intervals, fell in torrents; indeed, the roar of winds, and heavy peals of thunder, the successive and vivid flashes of lightning, laying bare the angry surface of the troubled waters, and presenting to the view, masts, ropes, rigging, and the men toiling upon the yards, and at the next moment all in darkness, imparted to the night a character of wild and terrific grandeur seldom surpassed.

To the green reefers, as the younger midshipmen are sometimes jocosely called on board a man-of-war, this was rather a rough introduction into the mysteries of their profession. Indeed, it may be doubted, if any protege of Neptune, even one of his eldest sons, could view, without concern, the high and soul-stirring sublimity of such a storm at sea; his stately ship, like a huge animal struggling with the elements, now poising on the top of a deeply undulatory wave, now sinking in the trough of the sea, and again rising and bursting through the phosphoric gleamings of the crested billow, and dashing the water from her sides, as the lion shakes the dewdrops from his mane.

As the morning dawned, the gale abated, and moderate breezes from the north succeeded, with a high and irregular sea. The latitude was 36° north, longitude 66'' west.

The metamorphosis which a vessel undergoes, after the abatement of a storm, is always a pleasant sight; and hence no sound is heard with more joy, on such occasions, than the vociferation of the boatswain, as "all hands make sail, ahoy!" is repeated by his mates through all parts of the vessel. To this call officers

|

|

and men respond with alacrity, as it is the harbinger of fine weather and clear skies. The stately topmasts of pine soon bear their flowing sheets, while the unfolding brails of the heavier sails add apparent dignity and strength to all below. Topgallant sails, royals, and studding sails, spread, as if by magic, their white surface to the breeze, and bright eyes, and. cheerful glee, show that the storm has sunk to rest.

Early on the morning of the twenty-first September, St. Antonio, one of the Cape de Verd islands, was in sight, bearing southeast, and about ten miles distant. This is the most western, or rather northwestern island, of the whole group, being in latitude 14° north, longitude 25° 30' west. The reefs were turned out of the topsails, with the view of keeping off, and, if possible, avoiding the calms which ships are liable to experience when they pass near this lofty island, some of the mountains of which are nearly as high as the Peak of Teneriffe. As a general remark, all vessels not wishing to touch at the Cape de Verds, should keep at least thirty miles to the west of St. Antonio, and thereby avoid the frequent calms which take place within ten or fifteen miles of the land.

The voyage of the Potomac, thus far, had not been very favourable, as her course had not been facilitated by any winds which were entitled to the appellation of trade. On the day following, the commodore stood in close with the island of Brava, the most southern of the group, and by far the most fruitful. Two boats were now despatched towards the shore, in charge of Lieutenant Pinkham, to procure, if possible, fruits and vegetables. The principal landing-place is on the northeast part of the island, though hopes were entertained that a landing might be effected on the west side, in the of&ng of which the Potomac lay.

After rowing several miles to the southeast, along the shore, without finding a single spot against which the sea did not break with violence, the boats were compelled to return to the frigate, Upon the sides of almost perpendicular mountains and cliffs, goats and monkeys were seen; the latter keeping up an incessant chattering, as if alarmed at the near approach of the boat towards their airy and solitary abode. But no human beings were visible, save two only, who were seated on a rock, fishing, in a state of perfect nudity. Thus failing in his intention of procuring

|

|

28 |

VOYAGE OF THE POTOMAC.

|

[October, |

refreshments, the commodore shaped his course for the capital of the Brazilian empire.

In approaching the equator, a rather unusual share of baffling winds and showers of rain were thought to prevail. In latitude of about three, north, on the night of Saturday, the first of October, a brilliant light was seen from the deck, in a northwest direction. Many believed it a vessel on fire; but on more attentive examination, it was found to be a whale-ship, "taking care" of the successful labours of the preceding day.

On the following morning, which was Sunday, the vessels were so near each other, that the commodore allowed a boat to be lowered, to board the whaler. She proved to be the ship Mercury, forty days from New-Bedford, bound to the Pacific; having had the good fortune to take a "hundred barrel" spermaceti, not a common circumstance; as, we believe, that of more than ten thousand a year taken by our ships, only four have been known to produce more than one hundred and twenty barrels.

This vessel, the Mercury, had been distinguished as the swiftest sailer in the South Sea fleet; and had gained no little notoriety in the year 1828, in a trial of speed with the United States frigate Brandywine, both leaving Payta, on the coast of Peru, and beating dead against the southerly tradewinds; in which contest the Mercury came out in advance. A similar trial of speed took place between the whaler and our own goodly ship, as win be seen directly.

At meridian, on the second of October, a sail was reported from aloft, directly ahead, and standing for us. At half past two, we had neared the stranger sufficiently to perceive that she was a clipper brig; and she, on her part, appeared to be satisfied with the view she had of the frigate, as she soon tacked, and stood on the same course as ourselves, which was directly opposite to her track when first discovered. At three, P. M., beat to quarters, and' run in the gun-deck guns, closed up the ports, and otherwise disguised the Potomac as a merchantman, as much as possible. It was about a four-knot breeze, and all the sail we could put on the ship to advantage, had been spread from the first of the chase; at dark we lost sight of her, about two points on our weather bow, and distant about five miles. The Mercury was now near us, on our weather quarter. We had gained considerably on the

|

|

1831.] |

CROSSING THE LINE.

|

29 |

chase, but not sufficiently to bring her within range of the eye after the night had set in. From that time until daylight, we tacked four times, endeavouring to get to windward, and intercepting what we had made up in our minds was a slaver; the Mercury following our motions, and keeping as near as she could. .

At daylight on Monday morning, the third, the Mercury was on our lee-beam, and, as our logbook expresses it, "the brig on our weather quarter." We were on the other tack immediately which brought us directly in her wake, and we felt assured that she could not escape us. Owing to the light wind, it was twelve o'clock (noon) before we came within hailing distance, when, as she showed no disposition to heave to, our colours were hoisted, and she was ordered by the commodore to do so, when she hoisted English colours, and immediately complied. Our boat was sent to board her; and, in a short time, returned with the information that she was the English brig Brothers, from Liverpool, bound to Pernambuco. Great was our surprise to learn from the captain, that that morning was the first of his seeing us! The chase of yesterday had escaped.

After several days of light winds and calms, a fine breeze from the southeast sprang up on Wednesday, the fifth. .Our friend the whaler, who was still near us, stood his ground for some time with the Potomac; while the speed of the latter did not exceed seven or eight miles an hour. But as the wind increased, the frigate began to draw ahead; and, from being, at nine o'clock, A. M., within gunshot, at three in the afternoon, he could only be seen, indistinctly, from the mast-head, astern! From this fact something could be inferred as to the good qualities of the Potomac.

On crossing the equator, there was nothing seen of Neptune or Amphitrite, in the process of inducting those of the crew who had never crossed the line, or been initiated into the mysteries of his marine highness. Commanders differ in opinion as to the propriety of permitting the "old sea-dog" to exercise his rough jokes upon those who are about to pass, for the first time, into the southern hemisphere.

We are not of that school who foresee ruin to the navy, and annihilation to commerce, because sailors have cut off their long

|

|

30 |

VOYAGE OF THE POTOMAC.

|

[October, |

queues, and, in a thousand other respects, are different from what they were an age ago; and the antique custom just alluded to, a relic of heathen superstition, without even the merit of classical embellishment to recommend, it, may be well dispensed with, as it must often do harm, and cannot, in any possible instance, be productive of good.

In an age like the present, distinguished for the march of improvement, and replete with discovery and advancement in every department of human science and knowledge; when a single day produces results which years could not have formerly effected, it cannot be expected that the sailor alone should remain uninfluenced by the revolutions which every thing else in the moral universe is perpetually undergoing. The changes which have been wrought in his manners and customs, have been most unquestionably for the better.

In illustration of this remark, it may be here mentioned, that, during the passage from New-York, great attention had been paid to drill the men in the exercise of the great guns. Every day, when the weather would permit, these exercises were performed; and, once a week, all went to general quarters, when all the exercises and manoeuvring of a regular attack and defence were carried through with the same precision as if the frigate were engaged in a real action with an enemy. A division of one hundred and fifty men, at this time, also, were being drilled to the use of the musket; and they evinced a readiness in the acquisition of this new species of seamanship, not to have been expected, from the generally supposed repugnance, on the part of Jack Tar, to the use of small arms; or to the acquirement of any accomplishment which more properly appertains to the soldier.

It is not strange, that, in the olden time, when sailors were dragged by force into involuntary servitude on board ships-of-war, and performed their allotted duties only at the point of the bayonet, that strong dislike should have been engendered against those who were mere tools in the hands of others, to enforce the observance of regulations to which they had never willingly subscribed. Shipping articles, in those days, were mere mockeries, and the marines were relied on to hold the sailors in bondage. It required time to smooth such asperities in the human breast, and hence, no doubt, arose the prejudice of the sailor to the life, char-

|

|

acter, and profession of the soldier. On board of the Potomac, this animosity did not seem to exist; or, if it did exist, its influence was but weak, as sailor and marine appeared to mingle together in peace and good-will, as men who might be required mutually to stand by and support each other.

Nothing material occurred until the morning of Sunday, the sixteenth, when the exhilarating announcement of "Land, ho!" from the mast-head, produced a new excitement through every part of the ship. It proved to be Cape Frio, or Cold Cape, as it is called, which bore west-northwest, forty -five miles distant; and at six, P. M., the same cape bore north by east, twenty-five miles distant. This cape is in latitude 23° 30', longitude 42° 2', about twenty leagues east of Rio Janeiro. The ship was hoven to, during the night, with her head to the south-and-east; the weather being cloudy, and the wind fresh. At about midnight, a vessel was seen to the eastward, but not near enough to be spoken.

In the morning, it was found that the current, which uniformly sets to the southward and westward along this part of the coast, together with a high sea, at this time heaving in the same direction, had borne the Potomac to the leeward of the entrance of the harbour of Rio Janeiro. While in the act of wearing ship, in the midst of a squall. Razor Island was discovered; and,immediately afterward, the breakers on Baga Island, while the thickness of the weather hid from view every other part of the coast. The instant these landmarks were recognised, the commodore ordered the ship brought upon the wind, on the starboard tack; and such confidence had he in her qualities to weather the island and enter the harbour, that he directed the mainsail, jib, and spanker to be set, in addition to the single-reefed topsails and foresail. It was a moment of some anxiety; and the Potomac, by occasionally immerging the muzzles of her gun-deck guns in the water, gave evidence of the powerful exertions she was making; though a strong weather-bow current was running, together with a heavy head sea. Still, her wake was as straight, apparently, as a clipper's; and, in an hour, the island was weathered, and, with square yards, she was brought to her anchorage in fine style. The maritime community were not a little surprised to see a frigate enter the harbour on such a morning, and in a living gale of wind.

|

|

32 |

VOYAGE OF THE POTOMAC.

|

[October, |

There were lying in the harbour at this time, his Britannic majesty's ship Dublin, a razee of fifty guns, thirty-two-pounders, Lord James Townsend in command; the Druid frigate. Captain Hamilton, and two sloops of war; a small Swedish frigate, and the French commodore, in a double banked frigate. Also, the Brazilian frigate Constitution, the only one in commission, bearing the broad pennant of Commodore Jewett.

From each of these vessels, officers were sent to the Potomac, offering to Commodore Downes, in the name of their commanders, such assistance as he might stand in need of. The Brazilian government, through an officer despatched to the proper authorities, immediately on the Potomac coming to anchor, congratulated the commodore on his safe arrival, and expressed their willingness to return the salute customary to be interchanged between nations at peace with each other. For the seventeen guns of the Potomac, nineteen were returned from the Brazilian fort. This was probably an error; if not, it was highly complimentary to our flag. Be this as it may, instances are not wanting, where the friendly feeling of these people has been made manifest towards the star-spangled banner of the United States. So far as our country had been represented at Rio by the lamented Tudor, the Brazilians could not be at a loss for a motive to pay the highest respect to our national flag. In the successor to this worthy man, we have been fortunate in having secured the services of the Honourable E. A. Brown, a ripe scholar, possessing every requisite qualification for usefulness in such a station.

Mr. Brown visited the Potomac during her stay at Rio, and was received with the salute usually given to the foreign representatives of our country. The hospitality of our consul, Mr. Wright, and of other American citizens resident in Rio, is gratefully recollected by the officers of the Potomac; and Mr. Brown, our charge d'affaires, seems to have made many friends by his urbanity and gentlemanly deportment. With these, the house of the Messrs. Burkitts was often visited with pleasure, and added not a little to the enjoyment of our officers during their stay at Rio.

The United States ship Lexington, Master-commandant Duncan, had arrived at Rio some time before the Potomac, in sixty-two days from Norfolk. Like the frigate, she had been disap-

|

|

1831.] |

CLAIMS ON BRAZIL.

|

33 |

pointed in meeting with the northeast trades; and had, also, experienced much calm weather near the equator.

Our claims on the Brazilian government have been adjusted. These claims were founded on a "few mistakes" which had occurred during the late war with Buenos Ayres, when the blockading squadron of the La Plata had appropriated to their own use and behoof sundry vessels and cargoes, belonging to sundry good citizens of the United States, who were navigating the high seas upon "their lawful occasions."

The British government was at this time urging its claims to indemnity for spoliations upon her commerce, committed under similar circumstances with those upon our own vessels; but, it would appear, with less success. Both parties were evidently growing warm upon the subject, and, but a short time previously, the commander of the British squadron threatened that he would blockade the port, and make reprisals. Whether the threat was officially communicated to the Brazilian government or not, we do not pretend to know; but the fleet did get under way, and proceed off the harbour; and, after backing and filling for a day or two in a rather menacing manner, returned to its original anchorage.

There were those who were ready, of course, to indulge in a. sarcastic smile at this manoeuvre of Admiral Baker, which, it appears, had not the desired effect, if it had been done for that purpose. The Cortez was at this time in session; and the claims preferred by the British government seemed to give rise to much excitement between the two parties.

"We have stated above, that our claims on the Brazilian government were adjusted; that is, the principle of settlement had been agreed on, though much in detail remained to be done.

|

|

34 |

VOYAGE OF THE POTOMAC.

|

[October, |

CHAPTER III.

| Harbour of Rio Janeiro and surrounding Scenery — Appearance of its entrance from the Offing — Its works of Defence — City of Rid, or St. Sebastian — Public Square) Facade, and Fountain — Public Buildings, Houses, and Shops — Paucity of Accommodations for Strangers — Climate, Food, and Health — Arcos de Carioco, or Grand Aqueduct — Discovery and Settlement of Brazil — Injustice to the Natives — Origin of the African Slave Trade — Discovery and settlement of Rio Janeiro — Emigration of the Royal Family — Their Return to Portugal — Civil Revolution in Brazil — Accession of Don Pedro — War with Buenos Ayres, terminated by ah unpopular Treaty — Abdication of Don Pedro — Insurrectionary Symptoms — Clerical Abuses — Population of Rio — Condition of the Slaves — Natural Productions — Theatrical fête on board the Potomac.

|

Had human agency been exercised in planning and' Constructing', for human use, the harbour of Rio Janeiro, it would be impossible to conceive a more felicitous result. It is a beautiful and capacious basin, imbosomed among elevated mountains, whose conical summits are reflected from the translucent surface of its quiet waters. The entrance is so narrow, and its granite barriers so bold, that it was, doubtless, often passed by early navigators, before it was suspected that such a retired and hidden inlet existed. To the aborigines of the country, it was known by a name corresponding to its character; for they called it "Hidden water," which, in their language, is expressed by the term Nithero-hy.

As this part of the Brazilian coast runs nearly east and west, the entrance of the harbour opens to the south, a few miles, of the tropic of Capricorn. It is defended by the Fort of Santa Cruz on the east, opposite to which are others of suitable strength, in vicinity of a high conical hill, called the "Sugarloaf," which some modern travellers have compared to the "leaning tower of Pisa.",

The entrance to this celebrated estuary, when seen from the offing, presents the appearance of a gap, or chasm, in the high ridge of mountains which skirt this part of the coast; and which, doubtless, once dammed up the waters within, until their continually accumulating weight burst the adamantine barrier which

|

View of Rio Janiero.

[Click to enlarge image]

|

|

1831.] |

RIO DE JANEIRO.

|

35 |

had hitherto held them in confinement, and, spurning farther restraint, forced a passage to the ocean. In the same manner, the Blue Ridge of Virginia was evidently rent in twain by the two united rivers, whose mingled waters now form the Potomac; and some suppose that the highlands of the Hudson once exhibited the same phenomenon. The fragments created by this convulsion of nature at Rio, are supposed to have been thrown into the sea, where they still remain, before the entrance of the harbour, in the form of a bar, on which there is never more than ten fathoms of water, while, just within it, there is not less than eighteen. However this may be, the chasm itself, as it now exists, presents a most picturesque appearance, opening as it does between two lofty mountains — Signal Hill on the right, the Sugarloaf cone on the left. These two remarkable piles of almost naked granite, present a striking contrast with the rest of the broken ridge, to which they now form abutments, as every other prominent part is covered with luxuriant vegetation.

On extending the view a little farther inland, the frowning batteries of Santa Cruz castle, With the Brazilian banner floating above them, are seen on the right, based on a solid rock of granite, thirty feet in height, projecting westwardly from the foot of Signal Hill. Opposite to this, on the left, eastwardly of Sugarloaf cone, .another fortress is discovered, of inferior strength; while between the two, but nearest to the latter, is a little island, strongly fortified, known by the appellation of Fort Lucia, which reduces the width of the passage to about three quarters of a mile; The Sugarloaf is said to be nearly seven hundred feet in height, and every accessible spot on that side the entrance is occupied by batteries, lines, and forts, or rather bears the evidence of having thus been occupied.

After passing all these naturally strong-holds, the harbour suddenly expands, and extends itself into a circular, or rather elliptical, inland lake, which- is sprinkled over with islands which

"Stand dress'd in living green;"

and surrounded by mountains rising in many ridges behind each other, like a vast natural amphitheatre. The tide rises in the harbour between four and five feet, and there is always sufficient depth of water to float vessels of the largest size.'

|

|

36 |

VOYAGE OF THE POTOMAC.

|

[October, |

The natural scenery which surrounds the harbour and city of Rio, has been frequently described, and often highly coloured by travellers. It is, indeed, beautiful to the eye; but, for our own part, we do not think that the meandering streams and gently murmuring rivulets of Brazil, pursue a more tortuous or fanciful course than those of the United States; nor can we perceive that their murmurings are, in the least degree, more "musically plaintive," or excite more tender emotions of the heart, than a creek of the Alleghany, or a small stream at the foot of the Stony Mountains, gurgling over the limestone pebbles, to pay its tributary mite to the majestic Missouri. Yet, among the objects that must arrest the attention on entering this majestic harbour, is the noble sheet of water, filling an oval basin of thirty miles in length and nearly fifteen in breadth, sufficiently capacious to contain all the fleets in the world — protected by a chain of mountains rising from its narrow mouth, and extending back, one above another, until the eye loses them amid white and fleecy clouds, which play in graceful curls around their airy summits. This view is certainly pleasing and exhilarating, and it is diversified, in many places, by cultivated spots, even to the highest elevation; while the valleys beneath are filled with the rich and rare fruits, peculiar to the tropics. The shores of this "emerald gemm'd" basin are also indented with numerous inlets, many of which are the mouths of rivulets that dash down the declivities ©f the mountains, as if eager to mingle with the tranquil waters of this great bay. Almost every eminence around it, as well as many of its islands, is crowned with a fort or a castellated parapet — a church — a convent — or a picturesque ruin.

Although the fortifications already alluded to completely protect, by their positions, the entrance of the harbour, the whole of which is commanded from within, by works long since erected on nearly all the surrounding heights and many of the islands, but now in ruins or ill repair; still, the defence of the place is thought to depend principally on a very strong fort, on the Ilha dos Cobras, or Snake Island, directly in front and near the north angle of the city, from which it is separated only by a deep channel of moderate width. This island is a solid rock, of about nine hundred feet in length, three hundred in breadth, and, at the point where the citadel stands, eighteen feet in height. All around, and

|

|

1831.] |

RIO DE JANEIRO.

|

37 |

close alongside of this strongly-fortified rock, which gradually declines, at one end, to within a few feet of the water, vessels of the largest burden may lie in perfect security. Here, also, are found wharves, dock-yards, magazines, arsenals, naval stores, a sheer-hulk, and many facilities for heaving down and careening vessels. Between Fort Lucia and the citadel is another fort, which commands the anchorage.

The site selected for the town by the early settlers, is, perhaps, the best that could have been chosen out of many excellent ones that everywhere present themselves. The city of Rio, otherwise called St. Sebastian, is situated on the southwest side of the harbour, or basin, about four miles from its entrance, and stands on a quadrangular peninsula, or square tongue of land, extending, on an inclined plane, a short distance into the bay. The town itself, which also exhibits the form of a parallelogram, and rises between four fortified eminences, which flank it at each corner, presents a northeast aspect of the basin, whose waters wash three sides of the square promontory on which it is built On a height flanking its eastern angle is a square fort, commanding and protecting stores of light ordnance, when deposited on the point below. Between this and the north angle of the peninsula, is a beautiful quay, built of solid blocks of chiselled granite, and forming an elegant facade in front of the city, and an eligible line for musketry and light cannon, to oppose the landing of an enemy's force, in case they should get possession of the harbour. On the north angle is another conspicuous eminence, on which stands the Benedictine convent, overlooking the island Dos Cobras on its east, from which it is separated only by a deep narrow channel, as before mentioned. On this side of the peninsula, near the water's edge, is a range of storehouses, overlooked by another square fort, flanking the west angle of the city, and commanding the imperial dock-yard beyond it. On the south angle of the town is the fourth eminence alluded to, on which is built the reservoir for receiving from the great aqueduct the water which supplies the city, and of which we shall speak presently. Between the last-mentioned eminence and the waters of the basin which wash the southeast side of the peninsula, is a public garden called the Passeo Publico, which is handsomely laid out in shrubberies, lawns, walks, and parterres.

|

|

38 |

VOYAGE OF THE POTOMAC.

|

[October, |

The city is well built, most of the houses being of stone, and the whole laid out in squares, the streets crossing each other at right angles. The palace, or imperial residence, faces the water; and with the open capacious square in front of it, one entire side of which it occupies, is in full view from the anchorage. This square, which is the first object that catches the attention of strangers, is surrounded on three of its sides with, buildings, while the fourth, which is bounded and lined by the stone quay, is open to the water. On the quay itself, near its central flight of stairs, which is the principal landing-place, in front of the square, is a beautiful fountain in the form of an obelisk, constructed, like the pier, of hewn granite; and from each of its four sides is constantly ejected a stream of pure limpid water, for the use of the lower part of the town, and the shipping in the harbour,

On advancing up the square from the landing, the visiter finds it paved with a smooth, solid surface, of the same kind of granite of which the obelisk and quay are constructed, and copiously sprinkled over with quartzose sand, which, together with the glistening mica of the Rio granite, is very trying to the eyes under the fervid rays of a tropical and sometimes vertical sun. The palace, which occupies the upper side of the square, though extensive in its dimensions, has nothing particularly magnificent in its appearance. The other public buildings, including the imperial chapel, a cathedral, churches, convents, nunneries, theatre, opera-house, &c., do not exhibit any imposing views of elegant architecture. Though originally built with much post and labour, no pains have been taken to keep them in repair. The streets are generally straight, but the most of them are narrow and dirty. The houses are commonly two stories high, with little wooden balconies in front of the upper windows, where the ladies sometimes present themselves, but not so frequently as in olden time, to throw flowers and nosegays at the foot passengers, or to listen to the nocturnal serenades of their lovers. But whether in Italy, Portugal, or Rio, latticed windows, without glass, always wear a dull and gloomy aspect to a traveller from England or the United States. The principal streets of Rio have flagged sidewalks, like those of our own cities.

The shops are generally large and commodious, and well supplied with English goods, and various other kinds of merchandise.

|

|

1831.] |

RIO DE JANEIRO.

|

39 |

Chinese goods can also be purchased here at a reasonable rate. There are many American and English merchants in the city, who, it is said, are doing a lucrative business; the export trade being almost entirely monopolized by them. The jewellers and lapidaries are principally found in Gold-street, which is the general resort of strangers who wish to procure articles in that line.

Although the city of Rio is the capital, and commercial emporium of the Brazilian empire, with a population of less than two hundred thousand souls, including slaves; and although it is constantly visited by merchants, traders, and travellers, from Asia, Europe, and the United States, speckling its harbours with the flags of almost every nation; yet it cannot boast of a hotel, coffee-house, inn, tavern, restaurateur, refectory, boarding-house, or any decent resort, at which strangers can procure refreshment, and a comfortable night's lodging. Comfort, indeed, even in the imperial palace, must be entirely out of the question, unless royalty enjoy some better protection from the attack of mosquitoes than the common republican curtains of network can afford; for if, by any accident, a single intruder find his way beneath the netting, wo betide the helpless sufferer within! Its rascally hum throughout the night, sometimes within a most threatening vicinity of the ear, is even worse than the puncture made in the skin with its sharp proboscis; for the latter will, at the most, but cause an irritating titillation, accompanied with a slight degree of swelling and some inflammation; but its tuneful serenade is a perpetual menace, that cannot fail to drive sleep from the pillow of one who is not drugged with poppies, or worn out with fatigue. These insects are troublesome enough in some portions of our own country, but here we console ourselves with the hope, that they will dearly pay for their temerity on the first appearance of an autumnal frost. But between the tropics they are immortal; or, at least, a new generation is constantly springing up to take the places of their progenitors; and, as with the fruits of the same climate, their existence is perennial.